With only 120 days to go until the Olympics, London is making the final preparations for what has been dubbed the first “sustainable games”. The picture below was taken from a viewpoint outside the conference centre and shows the Olympic stadium, the love-it-or-hate-it red ArcelorMittal Orbit sculpture and a newly installed wind turbine providing renewable energy to some of the Olympic venues. Great effort has gone into delivering a sustainable low-carbon games. London 2012 therefore provides an interesting case study to highlight the tensions and challenges that need to be addressed on a much larger scale to reduce our impact on the world and plan for future conditions. Anyone who has watched the BBC series Twenty Twelve knows that addressing these challenges leads to conversations that are ripe for comedy; I particularly like this clip (…and no, the wind turbine at the Olympic site was not turning when I took the picture below owing to rather pleasant high pressure conditions).

The final day of the conference began with an address by Irina Bokovo, the Director General of UNESCO. She reiterated the need for “systems thinking” in the context of planetary stewardship. The conference co-chairs presented a declaration on the State of the Planet (see conference website), described as a “living document” which will be a key part of the conference output to inform negotiations at the Rio+20 meeting. The declaration focuses on three areas of significant scientific progress over the last decade: the notion of the Anthropocene as a new geological epoch; the recognition of the interconnectedness between the environment, society and the economy; and the bringing together of social and natural sciences to provide policy relevant research and establish an evidence base for informing action.

Sybil Seitzinger, director of the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme, delivered a powerful address with some spectacular graphics illustrating both the complex nature of the challenges facing humanity and possible approaches to deliver solutions to combat these challenges. In particular, she commented on a recent study by Shindell et al. (2012) showing the win-win outcome of reducing methane and black carbon emissions on air quality in the short-term and climate change mitigation in the long-term. She also explained that the conference had made conscious decisions to reduce the meat content of food provided at lunch; I must admit, I was a little surprised to find only egg salad, cheese ploughmans and pepper and couscous sandwiches available on day 1. Quite honestly, it was a refreshing change from the “chicken or beef” options which typify the UCT food hall. Also to reduce waste lunch was given to delegates in brown bags rather than in the form of a buffet. Curiously, they measured nitrogen levels at the conference which were apparently 30% down on what they would have been if the usual amount of meat had been consumed.

The use of technology at the conference was impressive. In the plenary sessions questions from audience members and those watching online were put to speakers via twitter and read out from an ipad (of course). In response to a question on how international forums can reach agreement, Frank Biermann presented a big idea (“for a big challenge”) about the process of unilateral decision making. He claimed that the conventional consensus process was failing global society and a qualified majority voting system at the international policy scale could/should be introduced to prevent policy from being stifled. In the discussion that followed, it was commented that an alternative to the G20 based on population may be more advantageous, and ultimately more equitable, in improving the speed and scale of responses. I wonder how the climate science community might react to the suggestion that the IPCC be a majority led process rather than a consensus process? (…of course, I am not suggesting it – just an interesting thought exercise)

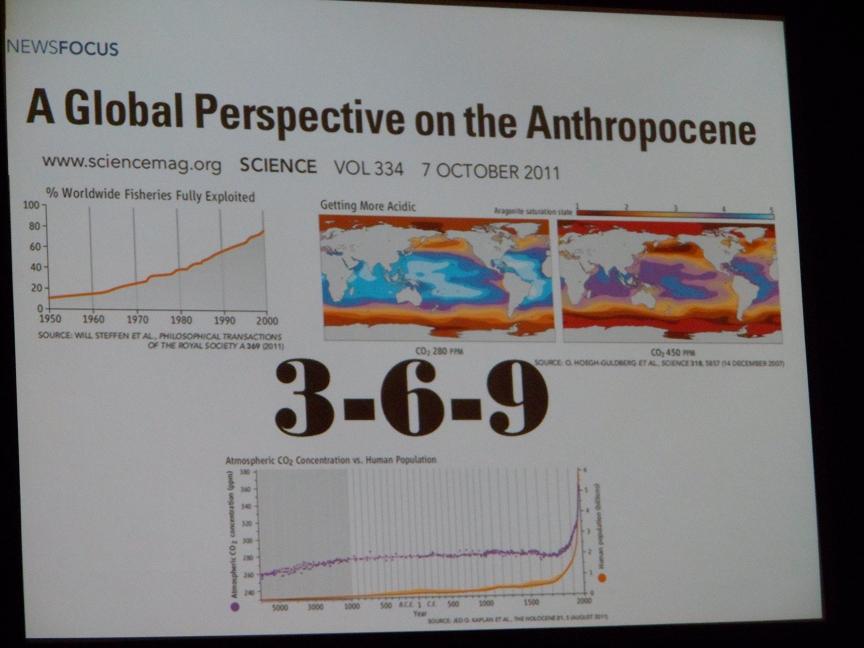

Despite the efforts of Sybil Seitzinger, slide of the day (below) goes to Johan Rockstrom who eloquently described the Future Earth project (you must realise that the slide of the day award is heavily affected by my inability to take good pictures of other equally suitable candidate slides). The “3-6-9” refers to the great challenges we face: a projected 3 degree increase in global mean temperature coupled with a 6th great extinction and a projected global population of 9 billion people by mid-century.

The format of the final day was slightly different to the other three days and the plenary session continued until lunch. Richard Noorgard presented an interesting economic analysis on where the world appears to be heading and where it really ought to be going. He suggested that in order to operate equitably within planetary limits, rich people will need to make sacrifices to help the poor and future generations; he did state that rich people could increase their standard of living but needed to be serious about the extent of their consumption. Noorgard cited a figure of $7.4 trillion which is estimated to be the ecological debt of the rich industrialised nations to poorer developing nations. He concluded his talk (which got at least three rounds of applause) by stating that we can’t look to the economy to design the necessary incentives to alter behaviour and that “prices reflect the economy we have, not the economy what we want to have”.

Oliver Morton from The Economist ably led a panel discussion focused on governance to end the final plenary session. Maria Ivanova, director of the Global Environmental Governance Project, initiated the debate defining governance as the “design and execution of policy”. An interesting discussion followed about the value-laden component of policy. Anne Glover, chief scientific advisor to the European Commission said that values are irrelevant to evidence, a sentiment I am not entirely convinced by given the often competing motives for gathering and disseminating evidence: exhibit A, courts of law. Glover expressed that we (the notion of who constitutes “we” led to some debate) have to use and respond to the evidence or we will fail as a species. I wonder whether there has ever been a period in human history where we have been required to act together as a species…sounds a bit too close to the film Independence Day for comfort!

In the final plenary session and indeed throughout the conference it has been stated that humans are becoming increasingly disconnected with nature. Oliver Morton (rightly in my opinion) questioned this notion stating that everyone is only a “breath away from nature”. I agree that we are becoming more urbanised as a society but surely we are also becoming more aware of global environmental issues given the increased focus in schools, the media and in online forums. One could argue (and I might be one of them) that as a global community we have never been more aware of nature and the value that Earth’s resources have for our lives and livelihoods.

I thought I’d end my summary of the conference with a photograph of the docklands area taken outside the conference centre. There is a lot of detail in the photo: Canary Wharf, the millennium dome, a plane (look closely) and a cable car (look even more closely) which is currently under construction to connect the Excel centre and the millennium dome for the opening of the Olympics. I guess the photo illustrates that society and our environment has and will continue to change dramatically. The infrastructure and decisions we make today with have a lasting impression on our landscape. What might this view look like in 10, 20 or even 50 years time?