Written By Anna Taylor

Feature image by Trish Sutherland

Cities around the world are increasingly recognized as hotspots of climate impacts, in addition to many being large sources of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. For cities to identify, prioritize and invest in climate adaptation measures that are suitable to their context, relevant information is needed about climate patterns impacting on the city, historically and into the future. Beyond such information being produced and available, capacities and mechanisms are needed to factor climate-related information into urban decision-making processes, together with many other sources of information and decision factors. The burning question is how to do this effectively and sustainably.

Critical to its use in decision-making is the translation of climate information into knowledge of the knock-on effects of climate impacts on the economic, social and physical functioning (or well-being) of the city and an understanding how significant (and costly) these cumulative effects might be under various scenarios. It is a solid understanding of the city-specific ramifications and the potential alternative courses of action that enable decision-makers to engage meaningfully with the climate-related information that is presented to them. Strengthening the capacity of those shaping urban decisions and those conducting climate research to make and articulate the significance of the many connections and feedbacks between the functioning of the atmosphere and the functioning of the city is at the heart of building climate resilience. The recent drought and water crisis faced by the City of Cape Town, as well as the towns of Beaufort West and Oudtshoorn, brought this into sharp relief. How can an evidence-base and understanding of such issues be built – including but not exclusively from a climate perspective – that enables suitable measures to be taken proactively?

What is climate information that is usable at the city scale by urban actors?

Climate information, in general, is generated through the accumulation, analysis and interpretation of data relating to climate conditions and changes over periods of 20 years and longer. It includes the results of analysing historical observations and future projections of biophysical climate variables (e.g. temperature, rainfall, air pressure, etc.), as well as related variables (e.g. surface run-off, soil moisture, sea levels, etc.). Climate information is based on both observed data from monitoring stations and satellites, and simulated data from running computational models. A broad definition of climate information could extend to variables and narratives of climate impacts, risks and vulnerabilities that are developed using biophysical climate variables as an input.

Climate information relevant to a city includes analyses of data relating to the area within a city’s spatial boundaries. It also includes analyses of data from beyond the city / municipal boundaries in places that are linked to, or have an impact on, the functioning of the city (e.g. rainfall patterns in catchments outside of the city where the city draws its water from). With regards to temporal scale, climate information that is relevant to the decisions being made by city governments includes information at the seasonal scale, for example how much rain might be expected for the upcoming season relative to the long-term average of that area, and information at a decadal scale, for example what the annual average temperature might be for the period 2040 to 2060 relative to that measured between 1980 and 2000. It is important to note that information on projected climate conditions for the coming 2 to 10 years timescales is very difficult to produce with any reliability because of natural variations arising from the chaotic nature of ocean-atmosphere interactions, the output of the sun and volcanic eruptions. This an active area of research, partly based on the recognition that this scale of climate information is what many city decision-makers are asking for, to align with terms of office, policy and strategic planning cycles and financing arrangements.

City decision-makers usually need locally specific climate information that goes beyond biophysical climate conditions and related risks to include information on outcomes relating to urban development and public service delivery, and the efficacy of strategies for addressing climate impacts. However, much of the available climate information still tends to focus on biophysical variables at coarser regional spatial scales and at time scales of 30 to 40 years and beyond.

How is climate information used by urban actors?

Previous studies focussing on cities and climate information, notably Mills et al. (2010), Grimmond et al. (2010), Ng (2012), Solecki et al. (2015) and Cortekar et al. (2016), point to applications in:

- Infrastructure planning (especially drainage, water, transport and energy infrastructure);

- Spatial planning and land use management;

- Building design (including building codes and standards);

- Water resource management;

- Transport planning;

- Open / green space and ecosystem management;

- Disaster risk management;

- Health services.

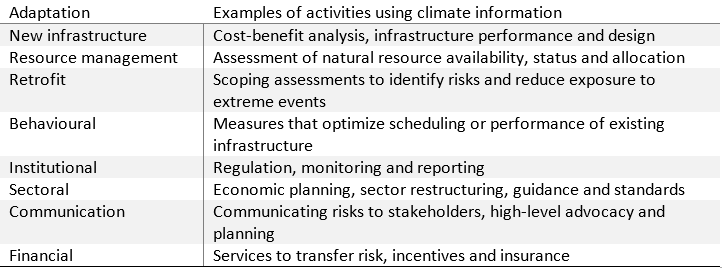

Wilby et al. (2009) provide a useful overview of the kinds of adaptation activities that require using climate information, see table 1.

Table 1: Examples of the uses of climate information to guide adaptation actions across various sectors that build climate resilience (Wilby et al., 2009, p.1196)

Studies conducted internationally agree that in most cases there remains a mismatch between the climate information produced by the science community and the needs for climate information by decision-makers. This mismatch is both in terms of the content of the information and the timing and format of its delivery. For climate information to be actionable it needs to be:

- Salient (i.e. striking or clearly of importance);

- Context sensitive;

- Based on accepted standards of practice;

- Seen as legitimate, coming from a source that is deemed worthy of trust;

- Helpful in clarifying areas for concern and intervention, expand alternatives, appraise options and improve outcomes of management decisions;

- Produced through iterative engagements with the intended information users (Cash et al., 2002; Pielke, 2007; Vogel et al., 2016).

What about the use of climate information in South African cities?

A piece of consultancy research was recently completed for South Africa National Treasury’s Cities Support Programme, commissioned through UCT’s African Centre for Cities, addressing the questions: How is climate information brought to bear on key city development and urban management decisions in South African metropolitan municipalities? And how can this be further strengthened? In addition to reviewing existing literature, the work entailed developing 4 case studies, namely City of Cape Town (1) revision of the Spatial Development Framework and (2) maintaining a corporate risk register; (3) eThekwini risk assessment for updating the city’s climate action plan to align with the ambitions of the Paris Agreement; (4) Mangaung climate change strategy. The case studies were based on 19 semi-structured interviews (with 10 city officials, 5 consultants and 4 researchers) conducted between July and November 2018. An overview of the findings are provided in table 2.

Table 2: Overview of four cases studies exploring the use of climate information in theplanning and decision making in three South Africna metropolitan municipalities

Comparing across the four cases reveals that cities access, interact with and use a variety of climate information, for various reasons in a multiplicity of ways that change over time. As such, it is important that we do not talk about delivering climate information to cities in any singular way. The research shows that the capacity of those involved in co-producing, translating and using the information is enhanced through iterative attempts at doing so, which is a long and slow process involving many actors over numerous years. Consequently sustained engagement is key to effective integration of climate information into urban decision making. In order to get policy traction on climate-related matter, climate information needs to be tailored to technical and political needs, within and across governance levels (e.g. city, province, national). The timing of when the information is brought into the decision making space and process matters greatly for ensuring the salience of the information is recognized. The translation of biophysical climate information into information about local risks, socio-economic impacts, adaptation measures and opportunities for urban value creation and city improvement is central to the application and use of the information in decision-making. But it is equally important to maintain links and thereby traceability back to underlying biophysical climate information, so that robustness and defensibility of conclusions and decisions reached can be checked and re-evaluated as new information becomes available.

The research suggests that key to generating actionable climate information and integrating it into decision-making is:

- Improving communication between climate information producers and those needing or wanting to use climate information, especially breaking historical patterns of a one-directional flow of communication from scientists to ‘users’ / decision makers. This relates to selecting appropriate biophysical and socio-economic variables / indicators to generate information about impacts and response measures at a scale that can be acted on.

- Building mutual trust between those involved in generating and using climate-related data and information (across organizations, sectors and scales) to establish the legitimacy of the process and thereby the ability to integrate the resulting products and outcomes into all relevant decision-making processes.

- Overcoming an initial lack of knowledge from all sides about what information is needed and best suited to addressing the unique problems and decisions in a particular context. Engaging repeatedly to enable iterative development and refinement of the information. And having the resources and staff capacity to do so.

- Persisting through various unsuccessful or only partially successful attempts as matching information supply with decision needs (because what is supplied is not targeted enough or because decision needs change).

- Reconciling the spatial and temporal scales of climate information and other decision factors.

- Grappling with technical and lay interpretations and implications of uncertainties and likelihoods. Translating climate risk and impact information into action on an iterative, progressive and coordinated basis.

- Navigating different approaches to problem formulation, problem solving and decision making, different organizational mandates and career incentives between technicians, scientists, managers and political actors.

The findings from the South African cases support this, highlighting that there is important experience to learn from but that lots is still required to do this more effectively within and between cities. For more details on these cases of climate information use in the South African context and the findings that emerge across them, please get in touch to access the full report commissioned by National Treasury’s Cities Support Programme. The report includes a set of recommendations for strengthening the use of climate information in key city development and urban management decision-making processes in South African metropolitan municipalities.

Kate Kloppers (formally Sutherland)

Hi Nicole, thanks you for the comment. Please see the last paragraph of the article for clarification. I will email you Anna Taylor’s contact details directly.

Nicola

There are some useful citations in here which I’d like to look further into, but as far as I can see no references. Is it possible to add these somewhere? Thanks!