On another unusually sunny and warm March day in London, the Excel Centre (above) played host to the second day of the Planet Under Pressure conference. The day began with an address by Yvo De Boer (former executive of the UNFCCC) who described that the key challenge for enabling green growth was decoupling human progress with the use and consumption of resources. Prof Bina Argawal from Delhi University followed, presenting an optimistic view of community led resilience to global environmental change stressing the value of cooperatives and collective action. To end the plenary, Richard Black from the BBC led a panel discussion on innovative solutions to the challenges being discussed at the conference (see picture below). Keith Clarke from Atkins got straight to the point with his comment that “the market is not moral” explaining that despite the rhetoric of business leaders, the market will only favour sustainable solutions if blunt instruments are introduced. Pamela Collins from École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne gave an interesting perspective stating that individuals often fail to act sustainably because they feel powerless to change global problems. She urged solutions to focus on empowering individuals rather than using the proverbial “stick” to change behaviour.

Before lunch I attended a very interesting session on adaptation strategies and disaster risk reduction. Dermot Grenham presented some work done at the LSE on microinsurance. Despite being interested in this field and studying at the LSE for two years, I hadn’t come across his work. Clearly effective communication within univesities and individual institutions is often as difficult as successfully communicating research to society! He set the context by stating that climate change was a driver of microinsurance demand and supply. However when I questioned him after the session, he admitted that microinsurance would be as valuable, and perhaps even more effective, if the climate was stationary. Terry Cannon from the Institute of Development Studies examined the space of research between development, adaptation and disaster risk reduction stating that the links are often weak. The good news is that the Africe Climate and Development Initiative (ACDI) at UCT appears to be improving these links, at least within Africa. He made the observation that solutions developed to address global change problems were rarely “problem defined” and all too often “institution defined” solutions, where those studying the problem devlop solutions linking direcetly to their specific interests and expertise, are deemed appropriate. This session also included an intersting talk from Sarah Aziz who spoke about translating “science speak” into “legal speak” (and back again) as well as a presentation from Carlos Welsh demonstrating that some Mexican communities are perhaps surprisingly resilient to climatic extremes because of well established community practices.

Over lunch I realised I had left my coat in the room where I had been sitting for the previous session. I hurriedly marched back into the room and because I felt to embarrased to simply grab my coat and leave, I decided to stay in the lunch time session that was taking place. It turned out to be quite interesting with a focus on exploring the implications of global environmental change in the health sector. Notably, a health specialist at IRI (Columbia University, NYC) commented that climate model led information was often not very tangible and was therefore rarely utilised in the health sector. She pointed towards the recent efforts in Ethiopia (see previous blog) suggesting that the dissemination of observational data and the provision of climate services provided a useful platform for informing health sector decision making.

In the afternoon I attended a session titled “Making Climate Science Useful”. As noted by the session convenor, this subject deserves its own conference and given the limited scope of the discussion that followed, I would certainly agree with her. The session consisted of a number of breakout groups led by selected individuals who each had to pitch to the audience encouraging people to join their discussion group. This left me with the feeling that I wanted to take part in more than one discussion and to be honest I was a little frustrated by the format. Perhaps it was just the group I chose to join (which focussed on the use of seasonal forecasts) but inevitably the discussion was dominated by those with the loudest voices. Nonetheless, some interesting discussion ensued and one comment that I found particularly interesting was that forecasters in many African National Met agencies are reluctant to issue probabilistic seasonal forecasts and preferred to give “best guess” forecasts. Personally, I feel that it is important for Met agencies to feel confident in issuing uncertainties with seasonal forecasts (and indeed longer time scale projections) in the form of probabilities or otherwise. There were also many comments regarding the need for science-based forecasts to be incorporated with indigenous knowledge and practise. Of course this sounds sensible but in the context of forecasting there is a risk that traditional and cultural ways of forecasting future seasons (i.e. the onset of seasonal rains) are contradictory to methods with scientific credibility. Should science information providers be encouraging people to act on the basis of evidence and indeed are traditional/cultural forecasting methods ever compatible or complimentary to science led methods?

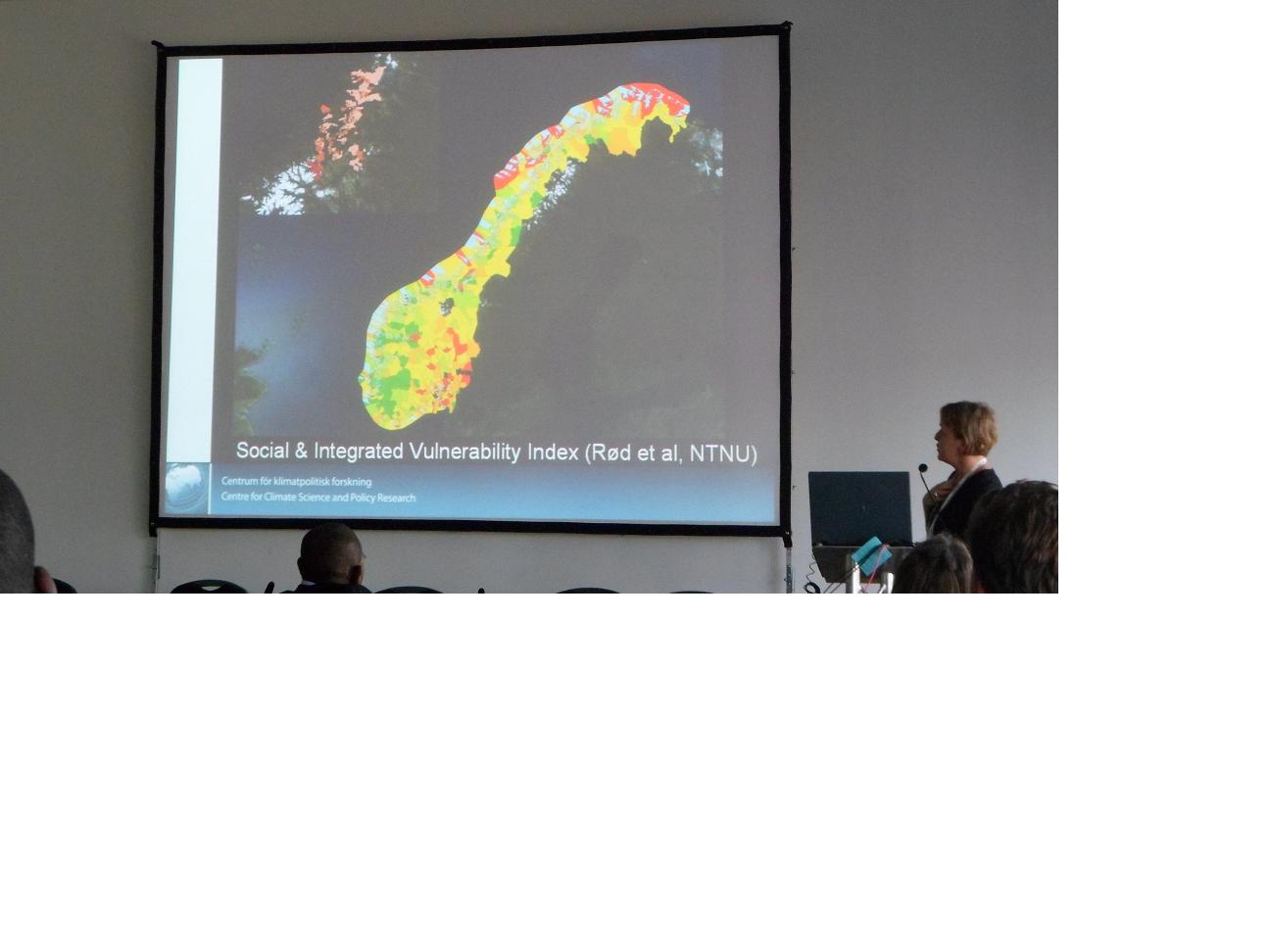

…and finally, slide of the day (well one slide from a series of good slides) goes to a speaker from the Nordic Centre for Climate Science and Policy Research: the slide (below) shows a vulnerability index for regions in Norway. Her talk was one of a series of talks forming a session about the prospects of information and communications techonology for sustainability in developing countries. Her work, and the work of her colleagues, demonstrated how visualisations and ICT can improve the interaction between information producers and users but she, and he fellow speakers, cautioned against the risks of misinterpreting seemingly attractive visual representations and stated that researchers must be reflexive about the approaches taken.

Joseph

I think this question relates to the “scientist” vs “consultant” dilemma that climate scientists are so often faced with. When issuing a forecast about the real world, a scientist must use evidence and theory which is based on scientifically defensible methodologies and analysis (e.g. validation or verification of models using observed data). On the other hand, a consultant has the freedom to…how can I say this…invoke creative license to issue forecasts which can be more suitably described as a “bet”. Operational weather forecasters (in my opinion) sit somewhere on the scientist/consultant divide. Whilst weather forecasts are predominantly based on models and observed data, the way forecasts are communicated using media, graphics and/or text are often adjusted based on forecasters preferences and past experiences. I know some weather forecasters who have their own preferences regarding which models to use, and their preferences are certainly not based on rigorous scientific analysis. So should a “climate forecaster” operate in the same way? On decadal to centennial time scales, I think the answer is unequivocally no. On seasonal time scales however, I think the answer is…it depends (bit of a cop-out perhaps). It depends on the knowledge of the scientist(s) regarding annual variability of the season in question and the skill of the model(s) on seasonal forecast time scales. However, given the current limitations and reliability of seasonal forecasts, the forecaster must be incredibly wary about making any kind of bet on seasonal time scales, particularly if the institution to which he/she belongs wants to uphold scientific credibility (e.g. case study: “BBQ summer” forecast – Met Office, 2009). Of course even when issuing a probabilistic forecast, one is still making a bet that the probabilities describe the real probability distribution. Given irreducible uncertainty in the initial state of the climate system, the best one can do is issue a probabilistic forecast – even with a perfect model (which annoyingly is still yet to be invented)!

Marky Mark

On seasonal forecasting I often hear the desire for more deterministic (at least sounding) forecasts, and sometimes this comes from the users of forecasts themselves. So should we continue to insist on the most scientifically defensible explanation when users may be asking us to ‘make a bet’ as to which outcome is more likely ?