On the third day of the conference, the focus shifted to solutions and how scientists might enable solutions to be enacted. In the morning I attended a session on adaptation dominated by presenters from Australia (which is no bad thing of course). Rohan Hamden gave an interesting talk about regional adaptation plans in south Australia. He commented that regional agreements sought to determine “least cost decisions” with a goal of establishing co-benefits for the local communities. Given the fact that many of the regions he discussed are in marginal locations where changes in climate could lead to profound impacts on the ability of humans and ecosystems to thrive, I wonder how effective “least cost” options might be. I am particularly interested to understand how “least cost” options might differ to “robust” options, which aim to be insensitive to uncertainty.

In the discussion that followed one person commented that institutions (specifically national meteorological agencies) often become “locked” into the process of improving climate forecasts by increasing model resolution. I am glad that others share this as a concern in the context of providing guidance for adaptation. As you may be aware from my previous posts, I am not convinced by the justification given for focussing computational and human resources on producing high resolution climate model data. Advocates of this approach argue that model information is irrelevant at lower resolutions. Whilst this may be true in many (perhaps most) cases, a high resolution projection in the absence of a detailed uncertainty analysis is scientifically naive. The desire to make climate model output look like remotely sensed observed weather might help in creating impressive images for glossy documents but do such projections really qualify as “useful information” for adaptation practitioners? One hopes that those making adaptation decisions are not captivated by the pretty colours and fail to acknowledge the uncertainties.

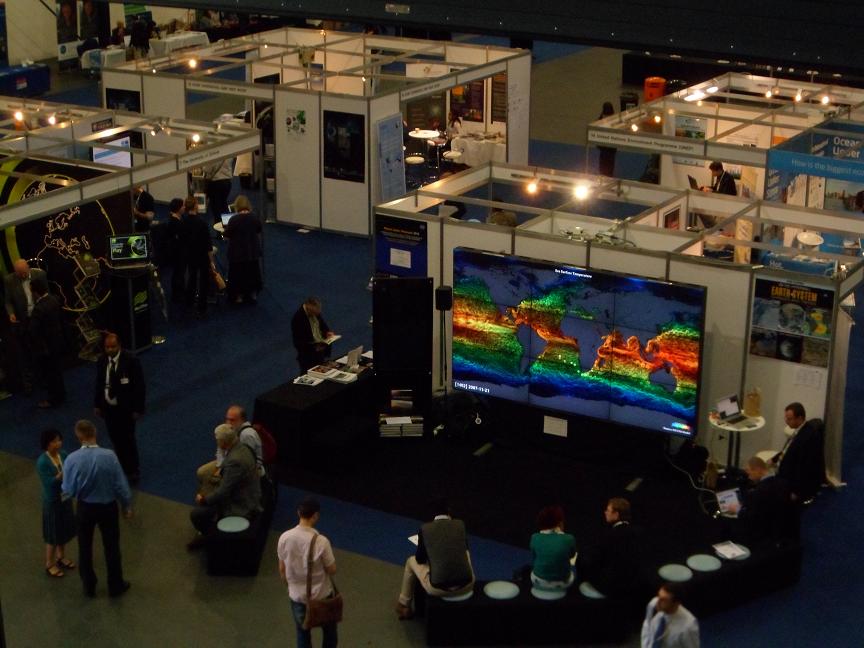

Certainly compared to most conferences, Planet Under Pressure has delivered some visual treats. I have seen a number of short films, cartoons and presentations using state-of-the-art graphics which has given a touch of class to the proceedings. Below is a birds-eye view of the exhibit area showing the impressive NASA hyperwall which mesmerised delegates throughout the week (the hyperwall has also featured at COP 17 and presumably many other science conferences). Thankfully, in addition to the polished nature of the conference, the content has also been fairly consistent.

“Convergent Global Megatrends”: with a session title like that I could not resist attending. To my delight, the session was also one of the most interesting of the week. The highly distinguished panel comprising Bob Watson, John Beddington, Pavel Kabat, Ed Barry (and other leading experts) enagaged in an insightful discussion chaired by Jim Hall from the Environmental Change Institute at Oxford University. Bob Watson stressed that an alternative to GDP is desperately needed to provide a measure of wealth that incorporates sustainability. Inevitably I was left wondering how one might derive an objective measure of sustainable GDP (suggestions welcome!). Ed Barry from the Population institute provided some daunting statistics about projections of global population in 2100. As in climate change discourse, the headline figures tend to focus on the mean/median/best guess values of 9 to 10 billion by 2100 whilst the actual projections span the range from 6 to 16 billion. Despite these uncertainties, John Beddington re-focused the discussion saying that over the next 15 to 20 years, a “politically tangible” time scale, the direction and variance of the trajectory for climate, population and urbanisation is clear; his comment that infinity is beyond the electoral cycle got a good laugh. There was also an interesting question and discussion regarding energy subsidies. According to Bob Watson (and the IEA) the global fossil fuel energy industry, worth some $6 to $8 trillion, receives government subsidies of $400 billion each year compared to $65 billion for renewable technologies (the global turnover of the renewable sector was not given). Clearly vested interests are effective in maintaining subsidies for established fossil fuel industries and it was suggested that governments should create “ministries for natural resources” to ensure that the governance structures acknowledge planetary boundaries. This idea links to one of the main sentiments shared by delegates throughout the conference. Chris Llewellyn Smith, director of energy research at Oxford, stated that universities needed to focus more on creating “systems thinkers” by adjusting the nature of taught modules for undergraduates. Promoting a systems perspective on global change challenges was reiterated in many of the conversations I encountered throughout the conference.