Honourable CSAGers,

Good evening, sanibonani, molweni, dumelang, riperile, ndimadekwana, goeienaand.

The year 2014 marked the publication of the Fifth Assessment report (AR5) by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). In keeping with the previous format, the report has been grouped into three working groups: Working Group I: the Physical Science Basis; Working Group II: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; and Working Group III: Mitigation of Climate Change.

These reports were first conceived in 1990, and have been published at regular intervals (of five to seven years) to provide a comprehensive review of the science of climate change. The Working Group I section of AR5 cited over 9200 peer-reviewed studies, and was compiled by over 600 contributing authors from 32 countries[1]. Increasingly, there has been a greater interest in regional climate projections, and considerable focus has been put on the climate dynamics of the African continent[2]. This leads to the question: how much of this research is being done by scientists based on the African continent?

To shed more light on this, we look at the history of publications in the Journal of Climate[3] as a proxy for the general trends in the field. This well-respected journal is consistently ranked in the top handful of journals for Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology, and is currently ranked second to only Atmospheric Chemistry & Physics in the field by eigenfactor[4] (a common metric for a journal’s impact and importance in its field[5]). In addition to this, the Journal of Climate has conveniently digitised articles into HTML format from 1997 onwards, and has an open access policy for articles older than five years.

After scraping all full-length articles (excluding comments and editorials) published in the Journal of Climate over the period 1997-2014, each affiliation listed in the articles was geocoded to obtain latitude and longitude coordinates. For simplicity, the analysis performed was purely on the basis of affiliation; no weighting was given to multiple authors with the same affiliation, or to authors with more than one listed affiliation. Due to inconsistencies with naming conventions, affiliations within 0.01° latitude/longitude (≅1km) of each other were grouped together.

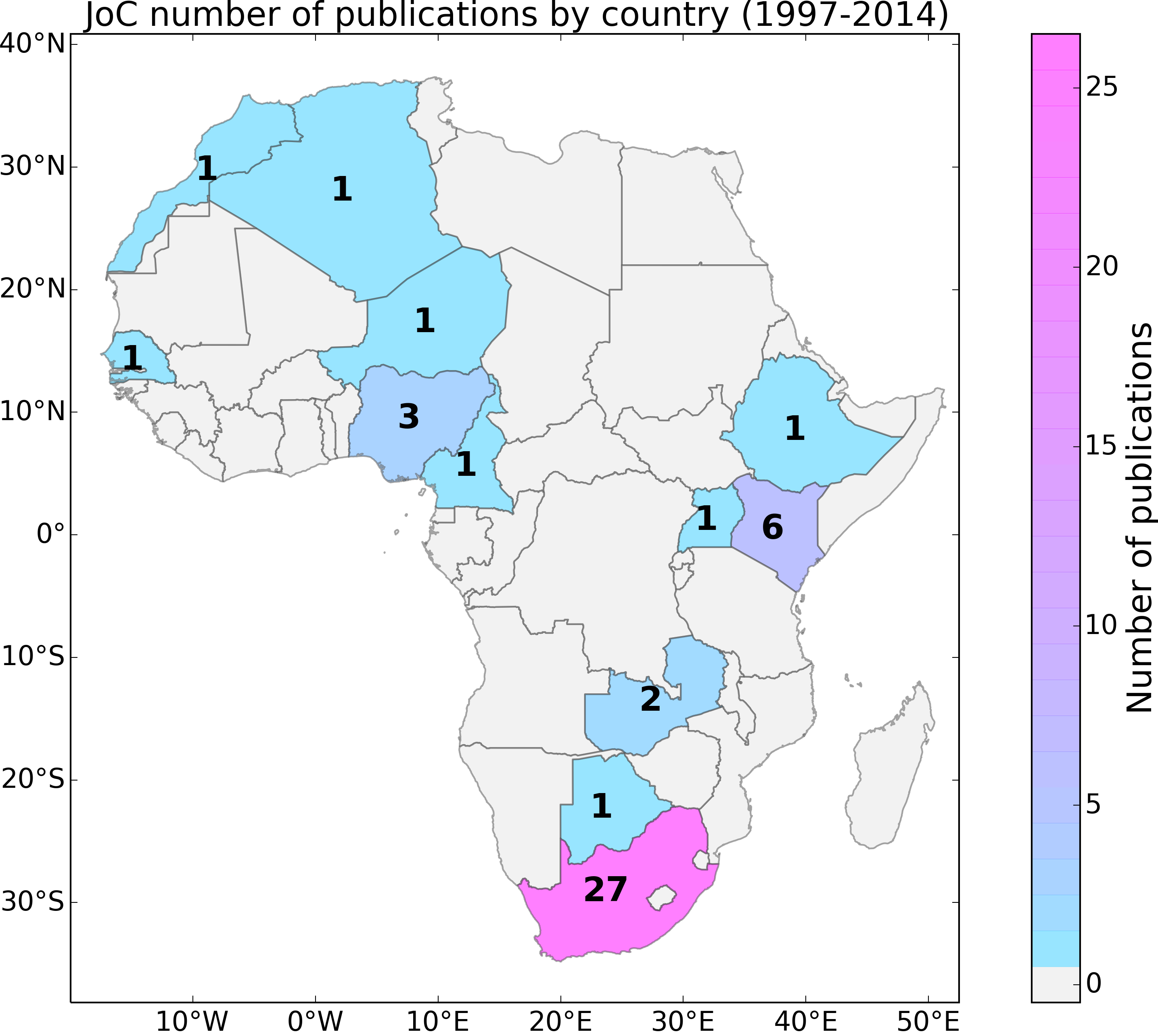

The results are suggestive of capacity gaps: of 6598 total publications over an 18-year period, there were just 46 publications from a total of 12 African countries (Figure 1). South Africa lead the way with 27 publications, followed by Kenya (6) and Nigeria (3).

Figure 1. Number of articles published in Journal of Climate from 1997 to 2014 with a listed affiliation in Africa.

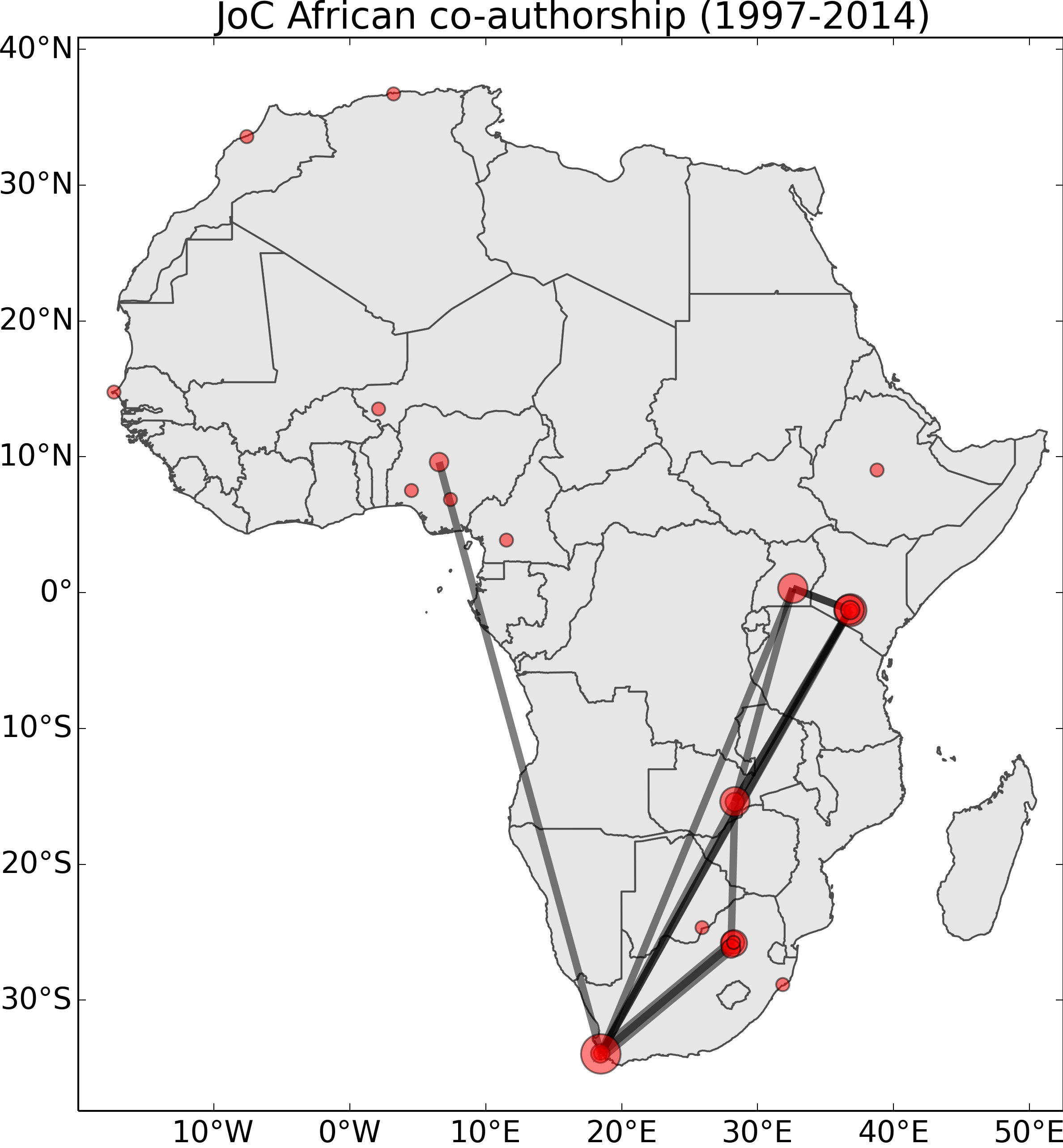

Looking at institutional relations, the relative isolation of many institutions is apparent (Figure 2). The majority of West African and North African countries have not co-authored articles with any other African institution. Institutions from the top publishing African countries also tend to collaborate more actively with each other. In particular, South African institutions such as University of Cape Town and the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research act as hubs for co-authorship.

Figure 2. Articles co-authored by African institutions in Journal of Climate from 1997 to 2014. Node size is proportional to number of links to different African institutions, and line width is proportional to number of articles co-authored with each institution. (N.B. Nearby nodes may overlap)

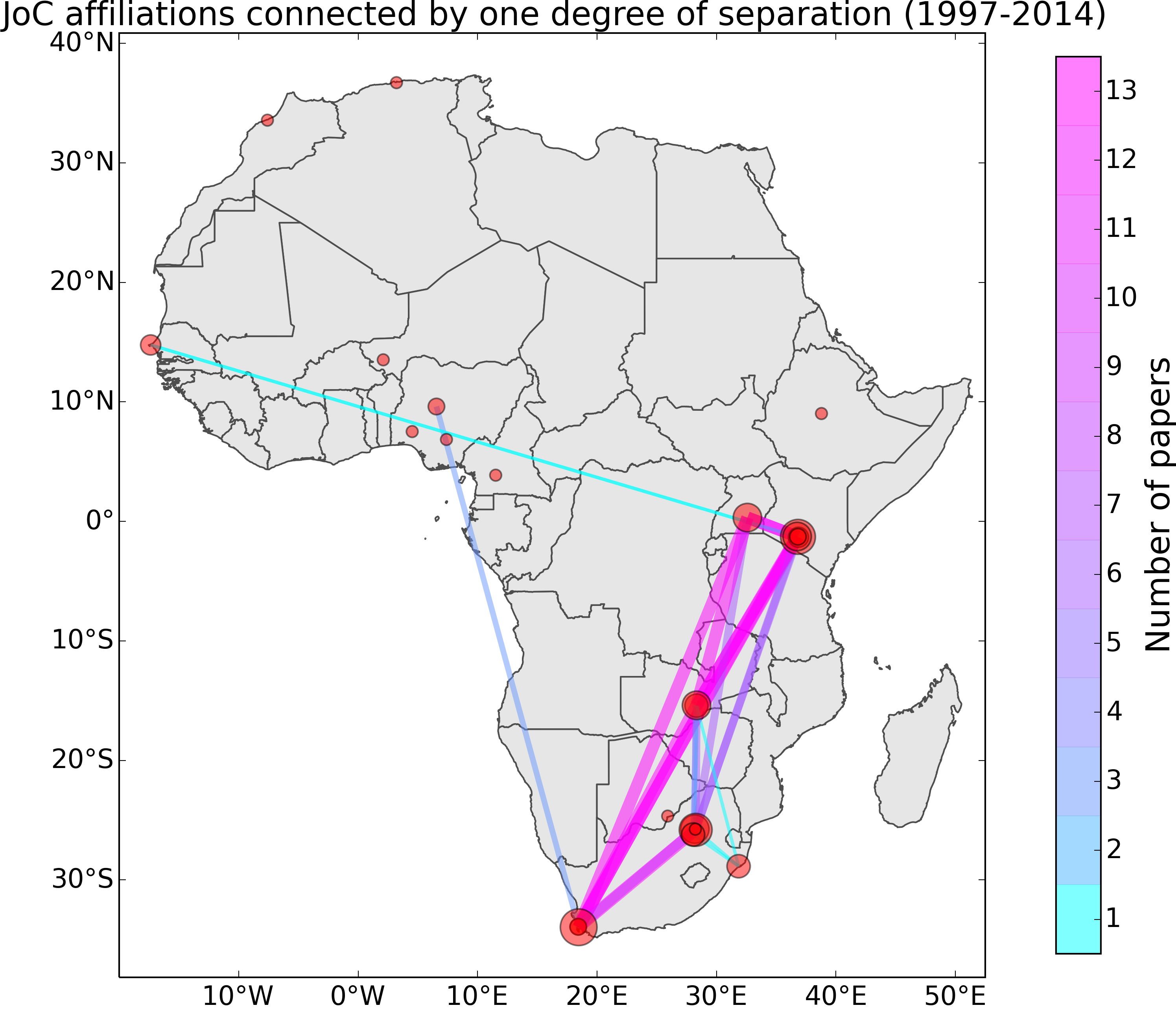

Is the lack of direct co-authorship a question of competing international funding? Looking at institutions linked by those institutions that have shared a mutual collaborator at some point (i.e. one degree of separation), there is an increase in linkages between East African and Southern African countries (Figure 3). However, these are a result of collaborations with South African institution, rather than external collaborators from outside Africa. This suggests that institutions aren’t working in the same fields, do not have established links with each other, or simply choose not to work together.

Figure 3. Articles published by African institutions in Journal of Climate from 1997 to 2014. Node size is proportional to the number of linked collaborators, and line width is proportional to number of articles linked by mutual authors. (N.B. Nearby nodes may overlap)

This state of affairs raises some questions. Are these numbers representative of the state of physical climate science in Africa? Is this an indication of “brain drain”, and if so, why are African scientists based abroad not collaborating with their “home” institutions? Are African scientists choosing to publish in other (lower ranked?) journals? Is the lack of collaboration between institutions a sign of ignorance, choice, or lack of opportunities?

References

1. IPCC. IPCC AR5: Working Group I Fact Sheet.; 2013. Available at: http://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg1/docs/WG1AR5_FactSheet.pdf. Accessed February 18, 2015.

2. CSAG. CORDEX. Available at: https://www.csag.uct.ac.za/research/cordex/. Accessed February 18, 2015.

3. AMS Journals Online. Journal of Climate. Available at: http://journals.ametsoc.org/loi/clim. Accessed February 18, 2015.

4. Thomson Reuters. InCites Journal Citation Reports. 2015. Available at: https://jcr.incites.thomsonreuters.com/JCRJournalHomeAction.action?pg=JRNLHOME&year=2013&edition=SCIE&categories=QQ. Accessed February 18, 2015.

5. Wikipedia. Eigenfactor. 2015. Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eigenfactor. Accessed February 18, 2015.

Modathir Zaroug

Many thanks Alex, very interesting and informative blog. You raised key questions in the last paragraph. Joseph added also some important questions.

Alex Shabala

Hi Joe,

That’s a good question. As a quick-and-dirty first approximation, we can count the number of times the word “Africa” appears in the body of the text (to dismiss affiliations).

It turns out that 10% (658) of the articles mention Africa at least 5 times, and 5.6% (371) mentions it at least 10 times. The count decay rate is approximately exponential after around 10 terms, so this is probably as good a guess as any for a threshold of Africa-focussed articles.

However, there’s no guarantee that the articles published by African-affiliated authors are about Africa either. The mean count for the Africa-affiliated articles is 32, but the standard deviation is 40! The median number is 15, so if we use that as a threshold, then the total fraction of output is 16.7% (46 out of 274).

Joseph Daron

Thanks for the thought-provoking blog Alex. I’d also be interested to know how many of the 6598 total publications in the Journal of Climate are focused on African climate? I’d assume this would be hard to disentangle in some cases, especially where the studies have global or multi-region focus. As a non-African scientist working at a non-African institution, but with an interest and research focus on climate in Africa, it has always intrigued me how much Africa-focused science is done by people who are from or reside elsewhere. It would also be interesting to further investigate the “brain drain” issue – could publications be used as a measure to further understand this?