Theory of change (ToC)… the concept strikes fear in the hearts of many people working in the field of development aid or applied research. Because of the poor application of this framework in many cases, it’s usually associated with additional, onerous tasks of visualising and mapping objectives and pathways towards these, as well as tracking outcomes according to this visualisation. It can also become a ‘tick box’ exercise in many cases; something that programmes return to each year with anxiety to squash their unexpected learnings into an outdated sketch.

For those working in complex, dynamic and emergent problem spaces (such as climate change risks in cities) through a transdisciplinary research (TDR) approach, it seems like a fruitless exercise to set objectives too far in advance. Other useful frameworks for designing TDR interventions that emphasise emergence, iteration and innovation have been put forward alongside the ToC. For example, Mitchell, Cordel and Fam (2014) suggest the Outcomes Spaces Framework as a way of imagining desired outcomes and ‘working backwards’, while van Breda and Swilling (2018) pose a set of guiding logistics and principles for TDR, applying abductive rather than deductive or inductive reasoning. As someone working predominantly in the TDR field, I think such guiding frameworks are very much needed to allow for experimentation and ‘uncovering alternatives’ in context, as described by van Breda and Swilling.

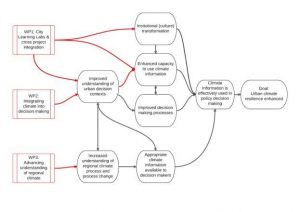

A recent experience with ToC has, however, reminded me about the value of ToC framework when applied with a critical perspective. The initial design of the Future Resilience of African CiTies and Lands (FRACTAL) ToC (Figure 1) was well thought out as a guiding tool, with the main aim of supporting decision making in southern African cities to better integrate climate change knowledge into decisions, thereby contributing to climate resilience. Main intended outcomes included; institutional (culture) transformation (which perhaps deviates most notably from pre-defined outcomes of similar projects), enhanced capacity to use climate information, improved understanding of urban decision contexts, increased understanding of regional climate process and process change, appropriate climate information available to decision makers and improved decision-making processes.

FRACTAL has been implemented across nine southern African cities with a variety of scientists, practitioners, decision makers and NGOs, supporting co-production of relevant and usable climate knowledge. TDR ethics are at the core of FRACTAL work. The first phase of FRACTAL finished in June 2019 and the team is currently gearing up to move into the second phase, during which questions of scaling the TDR co-production approaches that were implemented to support climate resilience learning (streamlining and sustaining) will be explored.

It must be noted that the FRACTAL Toc wasn’t effectively used or updated during the project, which is a fault of my own as the coordinator. But towards the end of 2019, we hosted a virtual learning retreat with researchers from across the cities, as well as some stakeholders who had been involved in the TDR process and critically reflected on our initial ToC (imagined pathways to impact), considered what we had learned and planned for the second phase. This learning experience was incredibly enriching for me and I think some of the take-home messages and questions that were surfaced during this reflection are relevant for others working in similar fields, so I’ve synthesised them and shared below.

Figure 1. Original FRACTAL Theory of Change (ToC) take #1 (2016)

Institutional (culture) transformation: The outcome of institutional culture transformation was envisioned for different types of organisations involved in FRACTAL TDR processes. The team expected the culture of research groups to shift for better understanding of pressures and priorities driving decisions in southern African cities, and the culture of decision makers to better consider future climate in planning. Anecdotal evidence from FRACTAL TDR activities points to similar changes across these two institutions as well as others that were involved in the activities; increased openness to ideas (and knowledge) of others, new ways of doing things, valuing diversity, a culture of inquiry, reflexivity, sharing, learning and collaborating. ‘Receptivity’ emerged as an important concept during FRACTAL, challenging the notion of ‘finding entry points for climate change information’ and supporting these cultural transformations.

Questions of scale were surfaced during the reflection; what is the relationship between individual, organisational and institutional shifts or transformations? What is the connection between learning, mindset and behaviour change (i.e. learning and action)? Anecdotal evidence suggests shifts in people who have participated closely in FRACTAL TDR activities learning labs but cities and municipalities, as functional entities, are somewhat locked into a particular way of working. If FRACTAL has indeed contributed to shifts in mindsets of individuals but has not shifted the institutional ways of working, is high staff turnover not a problem? These questions stick with us as we move into the next phase.

The team also grappled with what ‘transformation’ means compared with other types or scales of change. Evidence from Lusaka, Maputo and Windhoek suggests incremental changes towards cultural transformations. Global discourses related to climate change adaptation and transformation include such questions; the team hopes to contribute to these based on lessons from FRACTAL.

Enhanced capacity to use climate information: Experiences from FRACTAL point to the conclusion that this outcome is sorely outdated. A more appropriate outcome would be ‘enhanced capacity to interrogate, (co)produce and apply climate knowledge’. The reflection surfaced a suggestion to consider changes associated with this outcome at different time intervals. In the shorter term, projects such as FRACTAL should aim to support; i) capacity for understanding climate change information (uncertainty etc.); ii) relationships; and channels of communication for information sharing; and ii) building confidence of those making decisions to interrogate different sources of information and begin to home in on those that are relevant and significant for current decisions.

Stronger relationships between municipalities and other stakeholders (e.g. the Met office) have allowed collective interrogation of climate information during FRACTAL, as well as new, collaborative, proactive approaches to dealing with climate risks. For example, at the beginning of FRACTAL, the City of Gaborone (municipality) thought the climate change mandate belonged to a relevant national government body and that they, at the city level, should wait to receive information and action plans from this level. Now, at the end of the first phase of the project, the City of Gaborone takes responsibility for climate change issues alongside the national body and are hoping to include climate change information in their own plans. In the longer term, once the capacity, relationships and confidence has been built, city technocrats and councillors will hopefully be able to source relevant and significant climate change information to integrate into policies, plans, building, construction etc.

Improved understanding of urban decision contexts: One of FRACTAL’s main aim was to better understand decision making at the city scale, relevant to climate change and climate change issues (e.g. water or other resources), as well as the connections between the city and the region in which it sits. Social science research that was undertaken on urban governance, as well as TDR engagements in cities, helped all participants (including those living in cities) to better understand these decision contexts. For example, much decision-making power affecting cities still resides with national government, as well as the globalized private sector, so involving these stakeholders in TDR co-production activities should be a priority. The team also noted that the decision landscape in southern African cities is strongly linked to various sources of external finance. There is still much to learn about urban decision contexts of southern African cities relevant to climate risk and change; effort should be dedicated to this during the next phase.

Increased understanding of regional climate process and process change: Much of the climate science work in the first phase of FRACTAL focused on explaining and unpacking apparent contradictions in existing information, as well as methodological and conceptual approaches, with the main aim of making more confident statements about the future. This occurred through a more focused interrogation process to provide information in which the climate science team is confident. The need for restructuring this outcome emerged during the critical reflection, bearing in mind a critical question; how does innovative, fundamental climate science work (i.e. not assessing and repackaging existing information) fit into the overarching aim to increase resilience of cities? A big gap between the outputs of fundamental climate science and application of climate knowledge in the real world was noticed during the first phase of FRACTAL.

Appropriate climate information available to decision makers: Evidence from FRACTAL suggests that ‘appropriate’ climate information can only be produced in context. ‘Decision makers’ in any city comprise a large, heterogeneous group of people with varying mandates, values, backgrounds etc.; the appropriateness of or need for climate change information strongly links to the mandate of particular decision-making groups, as well as the stage of planning. Engagement in TDR co-production processes seems to be extremely important for participants to understand whether climate change information is appropriate and adds value to the decisions they are making. The FRACTAL team does, however, acknowledge the need to explore questions of scaling so that relevant information might be made available to those beyond the participants… important questions sitting with the team include inter alia; how can we produce climate change information that decision makers do not think of as ‘the answer’, but that rather motivates interrogation of information, as well as the process behind producing these products?

The outcome of ‘appropriate climate information available to decision makers’ is strongly linked to ‘distillation’ ; a core FRACTAL concept that will be further explored in the next phase.

Improved decision-making processes: The team reflected critically on the term ‘improved’, asking questions related to how this is judged. Based on evidence from FRACTAL, improved decision-making processes for supporting climate resilience in cities seem to be those that are more collaborative, democratic and inclusive, based on a deeper/stronger evidence base, and robust against a range of future scenarios.

The ‘formal decision-making methods’ (i.e. formulaic steps that provide options and guidance for making robust decisions) that were trialled in the first phase of FRACTAL didn’t prove very successful, at least in terms of the intended outcomes (i.e. adaptation options were not prioritised). The team reflected on how this is mostly because of the ‘messy’ decision landscape of southern African cities, with very many drivers of decisions to consider. The methods (e.g. Analytical Hierarchy Process) did, however, lead to unintended outcomes; the process of engaging stakeholders provided a space for deeper discussions and people stepped out of their silos, heard different perspectives and understood the drivers of decisions better.

What now?

The reflection exercise was extremely useful to consolidate and understand what we’ve learned from FRACTAL. It also allowed for abductive thinking as proposed by van Breda and Swilling (2018); many ‘theories’ of TDR for climate resilience learning have been proposed and will be tested in the next phase, but the team is well aware that these theories will shift and grow time and time again. The ToC will be reiterated based on these lessons and theories, and the team will use this updated version to guide research and action in the next phase, holding the boundaries of the new outcomes lightly.