Do you ever wonder how will the future, warmer world look like? What will changing climate bring upon us? No, not in terms of extreme temperatures, frequency of storms, magnitude of floods and sea levels rise, but in terms of our daily activities, relationships with our neighbours, workings of the community, city, nation, or all of the humanity. How will the warmer climate (and all the consequences thereof) affect what we eat, how we move about, where we live, how we communicate, what we expect from life, what we want for our children in the future? While we have means and tools to predict climate, albeit with some degree of uncertainty, we cannot really use similar techniques to provide answers to the above questions.

Part of the problem with predicting the “world” in the warmer climate is that the “world” evolves largely independently on climate. Our lives seem to be influenced very strongly by what we have created and what has little importance to our coping with climate and interactions with nature. Our contemporary lifestyle is defined amongst others by such ideas as the concept of a human being as an individual, culture of consumerism, globalization, gadgets, internet, urban life, tourism, games for the masses and religion. Climate was a much stronger determinant of lifestyles in the past, but a couple of simple inventions – fire, an air conditioner, a drain and a dyke – isolate us (well, for most of the time, anyway) from what the physics of the atmosphere cast in our direction. Global warming, however, brings climate back into our lives – by increasing risks of weather-related disasters, by imposing limitations on what technologies we use and how we use them, and by shaping our awareness of ambient world. How will these evolve, and how will our lives change with them?

Projecting technological and societal development that is conditioned on the changing climate might be possible if we look at technologies and the system of values we already have. We can foresee their evolution. We can foresee the evolution of a combustion engine car – this one is most probably on the ultimate way out to be replaced by electric or solar powered cars. But no doubt we will have technologies that we are not yet aware of. What if we learn how to teleport and we won’t need cars any more? This is not as an outrageous suggestion as one might think, actually. In his book “The Physics of the Impossible”, Michio Kaku classifies teleportation as “a class I impossibility” – it does not violate laws of physics, and may be possible within the next hundred years. Teleportation would surely be a climate-proof life changer, wouldn’t it? (well, that depends on the amount of energy it would require, of course.) Or what if we evolve to become homo arborplauduntis, realize the futility of senseless consumerism, and transform not just our industries but also drastically change our lifestyles? What would it be like to live in a global community of self-proclaimed tree-huggers?

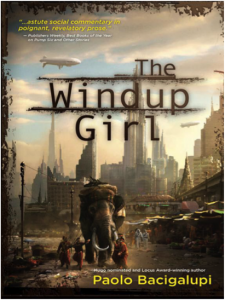

Such technological and societal predictions are really in the domain of futurists and science fiction writers. And this brings us to the main topic of this blog – two sci-fi stories by Paolo Bacigalupi that describe future world with somewhat different climate than we have today.

The first, “Windup Girl” is set in a post-apocalyptic Thailand a couple of hundreds years from now. The story revolves around lives of a genetically-modified human(oid?) trying to find her place in the society, a stalwart policeman set to lose his struggle against greed-fuelled tradesmen and politicians, an expat American commercial spy searching Thailand’s gene pool for something of use to an American company that monopolized world food production, and a Chinese emigrant just trying to survive in that weird, divided world. The apocalypse in Bacigalupi’s world was caused by a combination of changing climate and rampant spread of out-of-control diseases, a side effect of ubiquitous gene manipulation used in an attempt to feed the hungry world with dwindling natural resources. The direct climate impacts are not that dramatic – it’s hot, and Bangkok sits behind dykes, a couple of meters below sea level. Fossil fuels are gone. Methane is manufactured, but strictly rationed at a global scale (the city gets only enough to keep the pumps running). Otherwise the energy is all mechanical – world runs on springs, which are wound by humans or draught g-m animals. Cubed ice is a luxury that only the richest can afford.

The times described follow an era of “contraction”, so we see the world during an economic and social recovery. We see the world that has regressed, both economically and technologically. Well, we have to admit that converting solar radiation into other, portable forms of energy by means of organisms positioned at the high end of the food chain is not the most efficient way to do so. All our alternative energy sources (nuclear, solar, wind, geothermal) are not there (the author does not really explain why, though). Monopolized food production seems to be a counterintuitive extrapolation of recent trends towards global trade (although monopolization is in fact creeping in). This is not what we generally expect from our future, and there would be many who would argue that such a future is not realistic. But this is a cli-fi story, and not a reliable projection of a multi-model ensemble of models, so it does not have to be realistic. It has to be entertaining, and it should make us think. We’ve learned to associate the term “sci-fi” with perils and joys of space and time travel. But science fiction books (and movies) are not just about horrific marksmanship of imperial troopers on board the Death Star. They are a lot about human nature. The authors start with what they see around, with what it means to be a human being, they take as much cultural and historical baggage as they can, and then let their imagination wander. They put their heroes between weird machines or in a social system with drastically different principles to what we have today, often in distant (in space and time) worlds, and see what happens.

So what happened to us in the post-contraction, post apocalypse world created by Bacigalupi? Nothing, really. Humans in the “Windup girl” remain as “human” as we know it – diverse, divided, intolerant, nationalistic, greedy, corrupt, pervert. The era of contraction was no wake up call – we did not learn from the failure of our approach to manage the world. We adapted to the new reality, but only to the extent to which that adaptation was imposed by available resources and environmental conditions. We did not change our attitudes, our mindset, at least not with respect to the world that surrounds us. We stuck to the old ways – we live for personal gains, we are motivated by a mixture of cold calculation, national pride and cultural sentiment. This all makes for the “Windup girl” to be a rather depressing read.

The second story is “The Tamarisk Hunter”. The main character lives on the banks of the Colorado River in Utah, and his job is to remove vegetation from river valley in order to reduce evaporative losses and conserve water. A very noble job with a very human twist, and not in any way science-fiction like. The story becomes slightly out-of-this-world, however, when we learn that he actually gets paid in …water. He uses it to irrigate his garden to grow food to survive. It is the period of a “big-daddy drought”, which lasted for 20 years and does not seem to go away. And the legal struggle for access to whatever water the meager rainfall delivers to west of US has just ended. California, thanks to her superior lawyers, won, and has rights to all the rainfall that falls and water that flows through neighbouring states. These states, because they have no water to use, get depopulated, and essentially abandoned by the “civilized” society. We do not see in the story any sci-fi like technological advancement (or regression for that matter).

A realist within me asks: OK, Americans are litigious, but what happened to alternative technologies, what happened to sea-water desalination? (maybe this?). But again, we don’t really need that answer – it’s a cli-fi story, it does not have to be realistic, it is supposed to make us think. Currently, we tend to think that solutions to global warming are technological, and they will have a minor inflence on our lifestyles. Sometimes we think that climate-proofing will actually lead to a “better” world and healthier life. We think we can “engineer” our way out of the warmer world/greenhouse gas conundrum – we will design air-conditioned bus stops, more energy-efficient light-bulbs and cars, we will generate energy while we shop, we will nuke an asteroid to create a radiation shield around our planet. But what if solutions are not that easy? What if they require a radical transformation of the social landscape? And dramatic change in lifestyle? Let’s hope we will not have to find out, and the Bacigalupi’s worlds will all stay a cli-fi story.