I was fortunate enough to attend the Scoping dialogue for Resilience thinking and practice for development in Stellenbosch on 4 and 5 August 2016, which had four main objectives, namely: i) foster deeper understanding of resilience and resilience thinking; ii) explore and share how resilience ideas are being used in practice; iii) scope the possibilities and needs for building a regional partnership on resilience thinking; and iv) develop an agenda for how resilience concepts and practices can be used towards realizing transformative sustainable development pathways. The dialogue provided an opportunity to share ideas with researchers and academics who are grappling with similar conceptual and operational (tangible) challenges in the broad field of resilience.

After two days of deep thinking and discussions about resilience thinking and practice, I found myself driving home along the R310 on Friday evening feeling confused and perhaps even somewhat frustrated. Having returned to the world of academia fairly recently after a number of years focused on implementation, and as a self-proclaimed “recovering positivist” (to quote my colleague from the workshop) I’m in the process of clearly articulating my personal world views, and how these could or should shape my professional endeavors. A common theme in the last two events that I’ve attended (focused on adaptation to climate change and resilience) has been the evident need for fundamental shifts in the way we perceive the world, the knowledge we build, the mechanisms for development and the “frameworks” (for lack of a better word) for assessing our development goals. As I emphasized in my recent CSAG blog, the way we’ve been doing these things in the past and for the most part, the present, are not working, and the proof is in the pudding. Despite this growing recognition, we are in an awkward phase at the moment where few people or organisiations have the mandate, power or courage to influence “business as usual”, and the temporal cycles associated with policy and budgets aggravate this situation. We are a success-oriented society, driven by end goals and a constant desire to prove to ourselves, our community or our donors that things are working; that we’re moving forward through the maze (to where?).

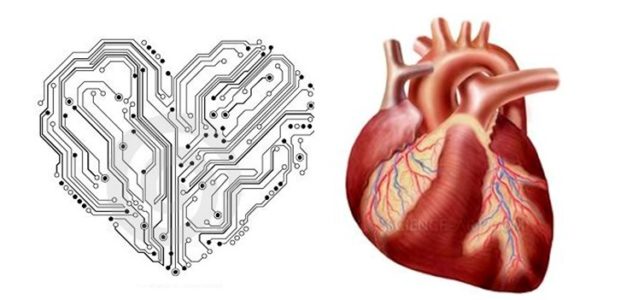

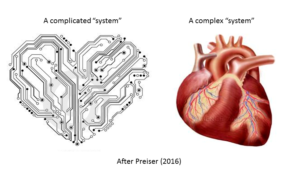

Three presentations were offered to set the scene for the resilience thinking dialogue: Anthropocene development challenges in Africa; the need for complexity thinking to manage such challenges, and the application of complexity thinking towards sustainable transformations. These opening presentations emphasized the call to move from viewing our world as a complicated space that can be mastered and controlled, to acknowledging complexity, thereby accepting that some questions will never be answered and many solutions might not be represented by equations or norms. Figures 1 and 2 represent the difference between how we might perceive a complicated and complex system. To respond to this call to acknowledge complexity, we need to constantly reflect inwards and outwards, practicing humility, authenticity and recognition of our “failures”, which are equally as important as our achievements. The problem is that we’re hard-wired to plug into a complicated world, constantly in motion towards an end goal, and few of us possess the time, bravery or even will (if it works for me then it works) to rebel against this.

I’ve heard mumblings of a revolution in the world of climate change adaptation and resilience, underpinned by the ideas of “transformation” or “transgression”, and I’m excited to be part of the associated meetings. There’s talk of throwing away words associated with “detailed design” or “monitoring and evaluation frameworks”, which assume a complicated instead of a complex system. However, this repositioning is messy and we are staring into the unknown, the navigation of which requires slowness and reflection. This shaky situation is further confused by the calls for immediate information and action to sustain as many people as possible in the precarious state into which we have driven ourselves. And in this context I find myself rambling: are our hands not tied by the big bosses, policies and budgets that govern the systems? When it comes to operationalizing concepts associated with complexity, are we really willing to swim upstream despite the discomfort we might feel? Considering the need for reflection and slowness in our complex world, is it simply not too late? And lastly, if I had not recently changed my career path and joined these discussions, would I have continued through the complicated maze forever?