I’ve been involved with the SARCOF process for a while, and this year I joined the event in Lusaka. For the uninitiated: SARCOF—the Southern African Regional Climate Outlook Forum—is a biannual gathering where forecasters from 16 SADC countries come together to produce a regional rainfall forecast for the upcoming rainy season.

I attended partly because I was contracted under an extension of the ClimSA project by the SADC Climate Services Centre to redevelop the software forecasters use to generate seasonal forecasts: the SADC Climate Forecasting Tool (CFT). SARCOF also links to one of our other projects—Acacia—so it was an opportunity to reconnect with forecasters across the region and see firsthand how climate information is shared between producers and users. In other words, I got to witness the messy but fascinating “coal face” of climate services.

The stress-testing of the CFT by actual forecasters went surprisingly well, although a bug or two were discovered – nothing detrimental, though. Overall – it was great to be able to contribute to brining the SARCOF forecast process to a different level – where forecast is methodologically sound and supported by solid skill evaluation. It was really satisfying to watch forecasters engage with the opportunities the new software offers: fast statistical forecasts from multiple predictors, one-click data downloads, and robust skill assessment. The Malagasy forecasters, for example, quickly produced a set of over 10 test forecasts using different predictor/domain combinations, which helped them choose the best approach for their final product.

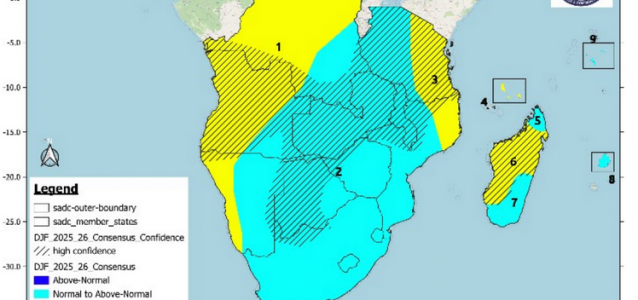

That said, this story isn’t really about the CFT—it’s about the SARCOF forecast itself. Its format is… let’s call it “unusual.” The region is divided into large zones, and each is classified into one of four categories: below-normal, normal-to-below-normal, normal-to-above-normal, or above-normal. Each category is tied to fixed tercile probabilities (e.g., 40/35/25 for below-normal). The point, I was told, is to always communicate some direction of seasonal anomalies. Even if the expectation is “normal,” the two “normal-to…” categories are intended to indicate the most likely departure from normal.

Why? Because, I was told, decision-makers (and users more broadly) don’t like a forecast of “normal,” which they see as uninformative. They also dislike forecasts that are climatological, or those with no demonstrable skill. In both cases, forecasters are told they’re not doing their job if they can’t provide an “informative” forecast. Forecasters also hedge their bets in this way likely helps forecasters avoid scrutiny from superiors if the forecast turns out wrong resulting in over 90% of SARCOF forecasts falling into the two “normal-to…” categories.

This mindset was clear in Lusaka. We heard comments like:

- “Don’t talk to me about probabilities—just tell me if it’s going to be wet or dry.”

- “For the water sector, a forecast that’s 60% accurate isn’t helpful—we need 90% assurance.”

- “Yes, the climate is chaotic, butterfly effect and all, but what are you doing to overcome this?”

These illustrate the difficult task forecasters face: balancing scientific defensibility with credibility, while also meeting the sometimes unrealistic expectations of their audience. They must strike a balance between the complexity of forecasts and the simplicity required for communication. It’s easier when speaking to a journalist or an NGO, but much harder when addressing a minister or director—when power dynamics come into play.

Even among the forecasters themselves, there’s division. Some advocate for a shift toward objective, skill-driven, probabilistic forecasts. Others prefer the familiar categorical approach, which feels intuitive and easier to communicate.

And honestly? I can see both sides.

The scientist in me says: “Be honest and precise. Show skill metrics. Communicate real probabilities. Stop hedging.”

But my 30 years of working with practitioners in southern Africa whisper something else: most users don’t have a strong grasp of probabilities, and the current categories—odd as they are—make intuitive sense. Change takes time, and it works best when it grows from within.

Ultimately, my advice to the forecasters is this: you need an honest discussion, and it shouldn’t just involve you. Users must be at the center. Where do you all want the forecasts to go? What will it take to build better user understanding? To challenge users to engage at a deeper level? Do you fully understand their needs and how forecasts fit into their decision-making? Is there scope to diversify forecast products to meet different users’ needs and capacities? What would it take to do that?

At CSAG, and through projects like Fractal and Acacia, we create spaces for exactly this kind of engagement—whether in Learning Labs or Test Beds—framed by the principle of co-production. SARCOF has started to introduce such approaches under ClimSA (which I was also involved in), and some progress has been made. But this year’s discussions showed there’s still a long way to go.

These SARCOF experiences remind me just how complex the producer–user space is: context, perceptions, skills, power dynamics… None of it is simple. Acknowledging that complexity is, hopefully, part of the path towards creating better, more informative forecast products – for the benefit of all.