Every year, the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), a division of the UN, produces a State of Food Security report. This year, a key focus of the report was on the role of climate extremes and variability in the recently observed rise in hunger globally. A number of CSAG researchers (Olivier Crespo, Christopher Jack, Mark Tadross, Pierre Kloppers, Bruce Hewitson Luleka Dlamini, Tichaona Mukunga, Khadra Ghedi Alasow, Fatima Mohamed and Kokesto Molepo) were involved in developing this component (part 2) of the report in collaboration with the European Joint Research Centre (JRC) and FAO.

You can access the full report here

You can watch the launch event and an interview with the coordinator of part 2 of the report Cindy Holleman here

Key messages emerging from the report:

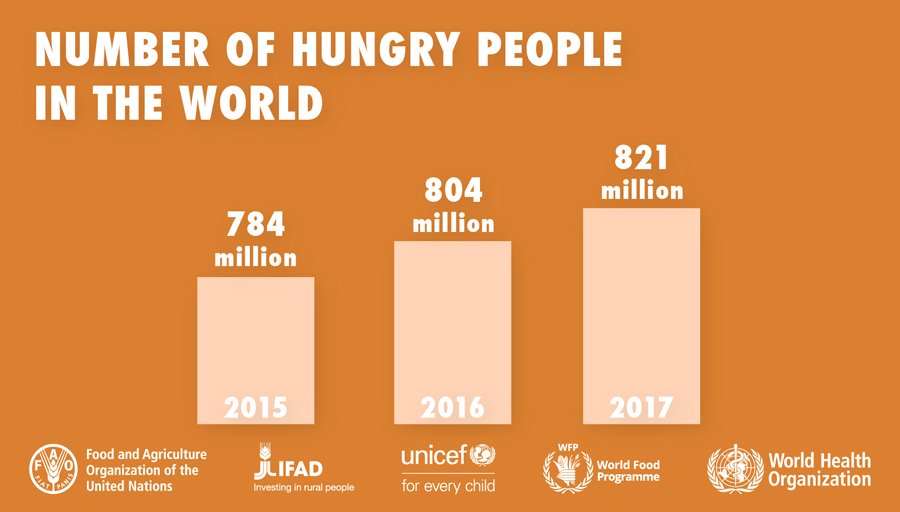

- New evidence continues to signal a rise in world hunger and a reversal of trends after a prolonged decline. In 2017 the number of undernourished people is estimated to have increased to 821 million – around one out of every nine people in the world. While some progress continues to be made in reducing child stunting, levels still remain unacceptably high. Nearly 151 million children under five – or over 22 percent – are affected by stunting in 2017.

- Wasting continues to affect over 50 million children under five in the world and these children are at increased risk of morbidity and mortality. Furthermore, over 38 million children under five are overweight.

- Adult obesity is worsening and more than one in eight adults in the world – or more than 672 million – is obese. Under nutrition and overweight and obesity coexist in many countries.

- Food insecurity contributes to overweight and obesity, as well as under nutrition, and high rates of these forms of malnutrition coexist in many countries. The higher cost of nutritious foods, the stress of living with food insecurity and physiological adaptations to food restriction help explain why food insecure families may have a higher risk of overweight and obesity.

- Poor access to food increases the risk of low birthweight and stunting in children, which are associated with higher risk of overweight and obesity later in life.

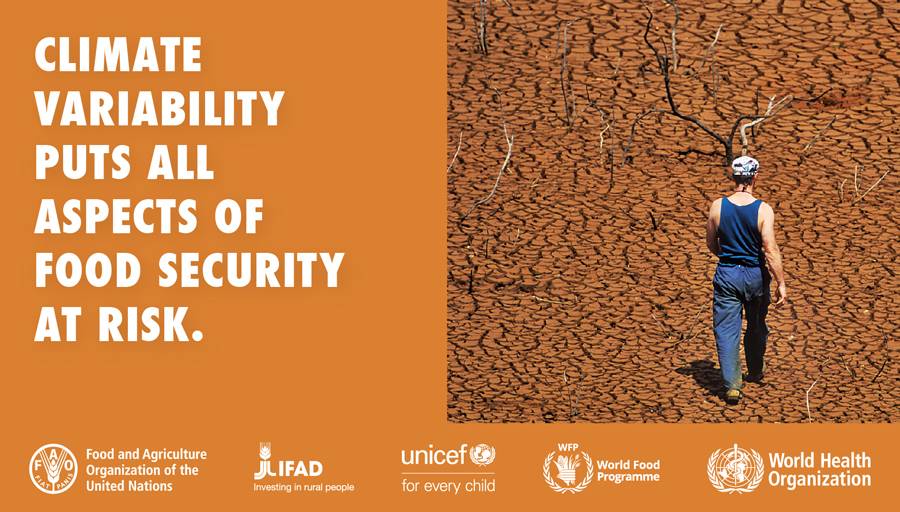

- Exposure to more complex, frequent and intense climate extremes is threatening to erode and reverse gains made in ending hunger and malnutrition.

- In addition to conflict, climate variability and extremes are among the key drivers behind the recent uptick in global hunger and one of the leading causes of severe food crises. The cumulative effect of changes in climate is undermining all dimensions of food security – food availability, access, utilization and stability.

- Nutrition is highly susceptible to changes in climate and bears a heavy burden as a result, as seen in the impaired nutrient quality and dietary diversity of foods produced and consumed, the impacts on water and sanitation, and the effects on patterns of health risks and disease, as well as changes in maternal care, child care and breastfeeding.

- Actions need to be accelerated and scaled up to strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity of food systems, people’s livelihoods, and nutrition in response to climate variability and extremes.

- Solutions require increased partnerships and multi-year, large-scale funding of integrated disaster risk reduction and management and climate change adaptation programmes that are short-, medium- and long-term in scope.

- The signs of increasing food insecurity and high levels of different forms of malnutrition are a clear warning of the urgent need for considerable additional work to ensure we “leave no one behind” on the road towards achieving the SDG goals on food security and nutrition.